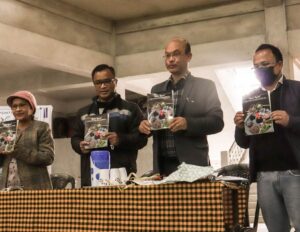

Located close to the Nokrek range in East Garo Hills is the small peaceful community of Mandal Nokwat. Though one passes through this village to get to the famous Nokrek National Park, very little attention is paid by passers-by to this pleasant settlement. The village is a close-knit community and lives in harmony with nature, with many interesting tales and history. The people of this village depend on farming for subsistence, and have abundance of agrobiodiversity in their vicinity. Mandal Nokwat is an active participating village of NESFAS and is currently taking part in the ongoing NESFAS project, “Empowering indigenous Communities through Agroecology Learning Circles (ALCs) for resilient, integrated and innovative natural resource management,” which is supported by MBMA and funded by the World Bank.

The community has an ALC group known by the name Awelwa ALC. Awelwa is the local name for tree beans or monkey beans. The name is aptly put as it is symbolic of indigenous identity and goes along with the community’s aim of reviving traditional knowledge and farming practices. At the onset of the project, the farmers of Awelwa ALC had prioritized the experiment of applying lime on the soil before the planting season, so as to reduce corm borer infestation in taro. To their dismay, they were faced with animal conflict, as their shifting fields were invaded and destroyed by hungry wild animals-elephants, wild boars, porcupines, that seem to have feasted on their crops hungrily. Caught in a big dilemma, the farmers guarded their shifting fields day in and day out and tried every trick they knew to ward off the animals. However, in this man versus wild conflict, the farmers stood no chance and were left with remnants of half-eaten melons, paw-prints, and resting shades in shambles.

Shattered by the destruction of their major means of subsistence, the community facilitator (CF) of Mandal Nokwat, Aipil R Marak took to alternate means of growing food and started a kitchen garden where he grew varieties of crops such as roselle, mustard, maize, brinjal, chillies, bitter dock etc. He made practical use of the knowledge passed on to him by his uncle. This was the use of a biopesticide using a mixture of different ingredients sourced from his surroundings. 250 grams each of Samaki, Alot (Phlogacanthus), Do·grikme (Serpentine Wood) and sada (tobacco) leaves were pounded to a fine paste and mixed thoroughly in 50 litres of water. This was then sprayed on the crops in his kitchen garden, which effectively eradicated multiple types of pests such as aphids, armyworm, white grub, pumpkin fly etc. that infected his crops to a significant extent.

When asked about whether he involved his ALC members in this project, the CF said, “This is a pilot experiment implemented after I recalled the method once taught to me by my uncle from Paromgre in South Garo Hills. I will mobilize my ALC members and share this knowledge with them so that they can also maintain kitchen gardens, and have an alternate means of subsistence.”

Though the community is still looking for answers to address the animal conflict in their shifting fields, it poses an important question for the rest of us- How do we tackle these conflicts without compromising the wildlife and biodiversity of nature while also providing the indigenous communities with viable sustainable livelihood opportunities?