Resilience and Sustainability of the Khasi Food System presented during the “Indigenous Peoples’ resilience, innovations and adaptation in face of the COVID-19 pandemic” webinar organised by the FAO, UN.

Indigenous Peoples have never been vulnerable; in fact, they are the living proof of human resilience. For thousands of years, Indigenous Peoples have lived in harmony with nature, developing dynamic and adaptive knowledge, know-how, skills, and practices to observe the environment, anticipate and respond to shocks. Their food systems, rooted in traditional knowledge have ensured nutrition diversity, food, and livelihood security throughout their lives.

However, as a result of the historic discrimination, injustice, and violation of their rights, Indigenous Peoples have been placed in various situations of vulnerability, even more so during the COVID-19 pandemic. The high degree of socio-economic marginalisation experienced by Indigenous Peoples has led to disproportionate risk in public health emergencies and to some extent, also weakened their food systems and resilience in times of crisis.

In a bid to help mitigate the negative effects of the pandemic along the food supply chain, the FAO, since October 2020 have conducted a series of webinars on Risk Communication and Community Engagement (RCCE). The latest of these webinars, “Indigenous Peoples’ resilience, innovations and adaptation in face of the COVID-19 pandemic” was held on the 10th of February 2022. The webinar sought its participants to discuss the role of traditional knowledge in the sustainability and resilience of Indigenous Peoples’ food systems, the disproportionate challenges faced by Indigenous Peoples during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as concrete examples of resilience and adaptation safeguarding their food and livelihoods security.

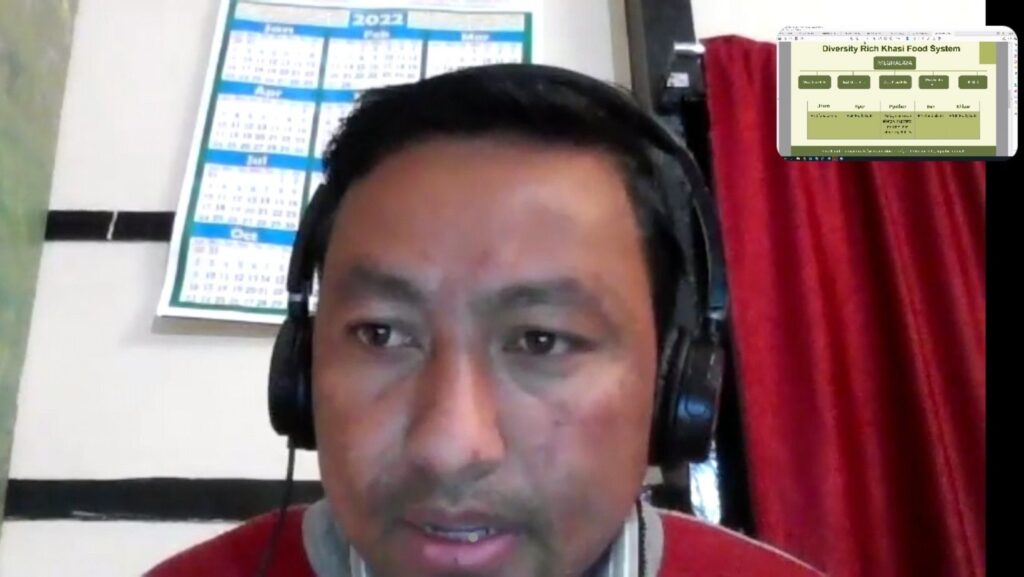

Bhogtoram Mawroh, Senior Associate, NESFAS was one of the panellists of the event representing the Khasi people of India and presented a brief discussion on “How the diversity of the Khasi food system in India supports the mitigation of COVID-19 impacts while ensuring communities’ food security?”

Bah Bhogtoram opened his discussion by stating how India continues to be one of the countries that have been worst affected by the pandemic. The effect of COVID-19 has also been felt in Meghalaya, his home state and home of the Khasi and Garo indigenous communities where more than 1500 people have been officially recorded to have died of COVID-19. He recounted how during the initial period of the lockdown, the disruption in the supply chain resulted in food shortages in the state. Normalcy was restored down the line but with an important takeaway as he states:

“The supply of essential items was restored over time by the shock experienced made many aware of the need to focus on the local food system.”

He then went on to share the details of the FIES (Food Insecurity Experience Scale) survey of June 2021 that was conducted by NESFAS in collaboration with FAO in 18 villages, 14 in Meghalaya, and 4 in Nagaland. The results of the study showed that moderate and severe food insecurity was only 11% compared to the more than 40% experienced in South Asia during the same period with severe food insecurity virtually inexistent in these communities. The moderate food insecurity experienced by these communities was similar to that of high-income countries like Europe, North America, and East Asia.

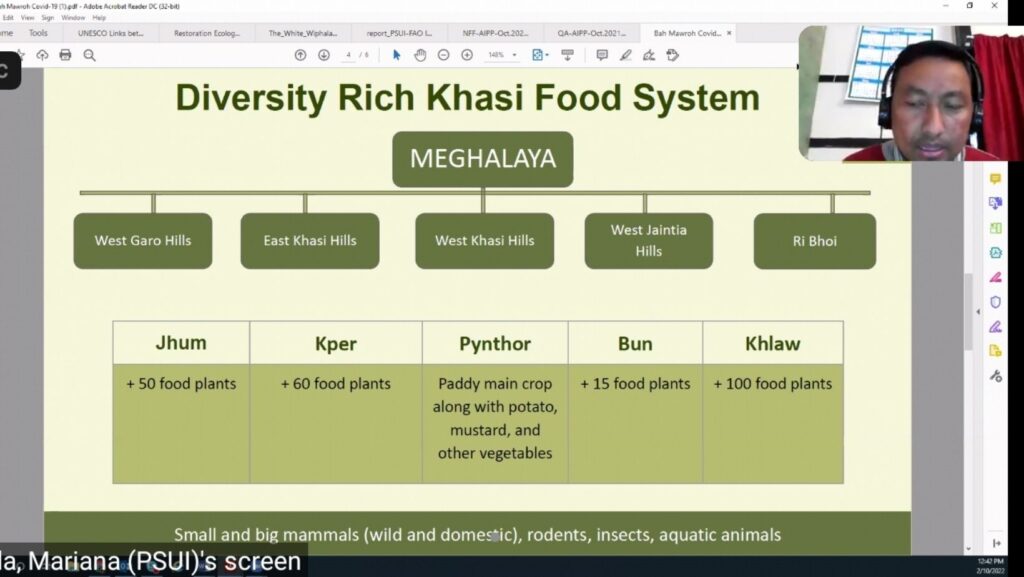

Bah Bhogtoram attributed this resilience to the diversity-rich Khasi food system before going on to share the four types of food systems are maintained by the indigenous communities in Meghalaya, viz., Jhum/Shifting cultivation, Kper/home garden, Pynthor/paddy system, bun/terrace farming, and Khlaw/forest. Most of these were ecologically self-regulating practices. He shared how the diversity of food plants from these systems ranged from one food system to the other. For example, in Jhum cultivation, more than 60 cultivated food plants are harvested while from the forest system, the plants harvested are usually more than 100.

This diversity of the Khasi Food Systems, Bah Bhogtoram stated, contributed hugely to the resilience to COVID-19 in four ways, viz.:

- Insurance against resource failures;

- Adaptation of food resources over longer time frames through evolutionary processes;

- Encouraging positive symbiotic interactions between species and areas in the landscape that support nutrient cycling, control pests and disease, and facilitate pollination;

- Sheltering the food system from the impact of ecological shocks.

Mawroh added how the indigenous communities also adopted certain practices to combat the problem of food shortage; such as reviving the cultivation of hill rice, greater dependence on wild food, and food sharing: “These practices allowed the Khasi community to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 and ensure food security.” he added.

Bah Bhogtoram expressed that the diversity embedded in Indigenous peoples’ food systems, of which the Khasi food system is also a part, can help in mitigation and adaptation to various crises including COVID-19. He concluded by reasoning that the experience shared during the webinar reiterates the need to support Indigenous Peoples’ food systems for building a more resilient and sustainable global food system.